On the cover: RSA Encryption

If you’ve ever shopped online, sent a private message, or connected to a secure website, you’ve probably used RSA encryption without even knowing it. RSA was founded by three mathematicians Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) from MIT after whom it’s named. RSA is one of the most famous cryptographic systems, and what makes it magical is this:

You can tell the whole world how to lock a message for you, but only you can unlock it.

This blog is a beginner-friendly walk-through of how that’s possible, and why a couple of large prime numbers hold the entire system together.

The Padlock Story (Simon Singh’s analogy)

Imagine you want to send me a secret message by mail.

- I send you an open padlock - but keep the key with me.

- You put your message in a box, lock it with my padlock, and send it back.

- Because the box is locked, only I (who has the key) can open it.

The magic is:

- You never got my private key.

- Anyone can lock a box for me, but no one else can open it.

RSA works on the same idea, except the padlock is just a big number called n, and the way to lock something is using a public number e. In the context of Computers, the padlock is called a public key and the secure key is called a private key. Also, this analogy is taken from the book Fermat’s Last Theorem by Simon Singh. Definitely recommend!

The Ingredients

- Two large prime numbers: $p$ and $q$ of the order of 100s of digits (We keep these secret.)

- Their product: $n = p \times q$ (This is the “padlock” - we give this to everyone.)

- Euler’s Totient: $\varphi(n) = (p-1) \times (q-1)$ (This is used for building the key.)

-

Public exponent: $e$

- A small number that’s coprime to $\varphi(n)$ - often 3, 17, or 65537.

- This is the “how to lock the box” number.

- We give out both $n$ and $e$ to the world. This is totally safe - knowing $n$ and $e$ doesn’t help anyone find $p$ and $q$ if they’re large enough.

Why We Give Out e (and n)

If we didn’t give $e$, people wouldn’t know how to lock messages for us.

Think of $n$ as the shape of the padlock, and $e$ as the turning method. Both are needed to lock something, but only the person with $d$ (the private key) can reverse it.

Mathematically:

- Public key = $(e, n)$

- Private key = $(d, n)$

-

$d$ is computed from $e$ and $\varphi(n)$ using the modular inverse:

\[e \times d \equiv 1 \ (\text{mod} \ \varphi(n))\] -

NOTE: The $c = a \ (\text{mod} \ b)$ just means that the remainder when $a$ is divided by $b$ is $c$.

-

NOTE: This $a \equiv b \ (\text{mod} \ n)$ just means that $a$ and $b$ have the same remainder when divided by $n$.

- NOTE: The $\gcd(a,b)$ just means the greatest common divisor of $a$ and $b$.

The Core Encryption and Decryption

-

Encryption (locking the box):

\[C \equiv M^e \ (\text{mod} \ n)\]Where:

- $M$ is your message (as a number),

- $C$ is the encrypted message.

-

Decryption (unlocking the box):

\[M \equiv C^d \ (\text{mod} \ n)\]So you get back your message at your end!

Mathematical Intuition

All this is good, but why does this work? All because of a nice Euler’s theorem, and the way we pick the $e$ and $d$. To be more concrete, let’s go over what we do step by step:

- Pick two primes $p, q$ and set $n = pq$.

- Compute the Euler’s totient, $\varphi(n) = (p-1)(q-1)$.

- Choose $e$ such that $\gcd(e,\varphi(n))=1$, i.e. $e$ and $\varphi(n)$ are coprime.

- Choose $d$ as the modular inverse of $e$ modulo $\varphi(n)$, i.e. $ed \equiv 1 \pmod{\varphi(n)} \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad ed = 1 + k\,\varphi(n)\ \text{for some integer }k.$

Encryption is $C \equiv M^e \pmod n$.

Decryption claims $M \equiv C^d \pmod n$.

Why is that true?

Consider the product exponent $ed$:

\[M^{ed} \;=\; M^{1+k\varphi(n)} \;=\; M \cdot \big(M^{\varphi(n)}\big)^k.\]Euler’s theorem says: if $\gcd(M,n)=1$, then

\[M^{\varphi(n)} \equiv 1 \pmod n.\]Plug that in:

\[M^{ed} \equiv M \cdot \big(M^{\varphi(n)}\big)^k \equiv M \cdot 1^k \equiv M \pmod n.\]But $C \equiv M^e \pmod n$, so

\[C^d \equiv (M^e)^d \equiv M^{ed} \equiv M \pmod n.\]That’s the whole trick: picking $d$ so that $ed \equiv 1 \pmod{\varphi(n)}$ makes exponentiation “undo” itself.

what if $M$ shares a factor with $n$? (edge cases)

If $M$ is divisible by $p$ or $q$, the above Euler’s theorm “$\gcd(M,n)=1$” assumption breaks. But RSA still works! The clean way to see it is to check the congruence mod $p$ and mod $q$ separately and then combine them (Chinese Remainder Theorem):

If $p \mid M$, then $M \equiv 0 \pmod p$, so trivially $M^{ed} \equiv 0 \equiv M \pmod p$.

If $p \nmid M$, we can use Fermat’s little theorem: $M^{p-1} \equiv 1 \pmod p$.

\[M^{p-1} \equiv 1 \pmod p.\]Now raise $M$ to the power $ed$:

\[M^{ed} = M^{1 + m(p-1)}.\]Split it:

\[M^{ed} = M \cdot \big(M^{p-1}\big)^m.\]Since $M^{p-1} \equiv 1 \pmod p$:

\[\big(M^{p-1}\big)^m \equiv 1^m \equiv 1 \pmod p.\]So:

\[M^{ed} \equiv M \cdot 1 \equiv M \pmod p.\]Because $ed = 1 + k(p-1)(q-1)$, $ed \equiv 1 \pmod{p-1}$, so $M^{ed} \equiv M \pmod p$.

Put the two congruences for $p$ and $q$ together → $M^{ed} \equiv M \pmod n$.

So the decryption step is valid for all $M \in {0,\dots,n-1}$.

A Small Example (for us measely humans)

Let’s pick tiny numbers (not secure at all):

- $p = 5$, $q = 11$

- $n = 55$

- $\varphi(n) = (5-1) \times (11-1) = 4 \times 10 = 40$

- Pick $e = 3$ (coprime to 40)

- Find $d$ such that $3d \equiv 1 \ (\text{mod} \ 40)$ → $d = 27$

Public key: $(e=3, n=55)$ Private key: $(d=27, n=55)$

Say we want to encrypt $M = 12$:

-

Encrypt: $C = 12^3 \ \text{mod} \ 55 = 1728 \ \text{mod} \ 55 = 23$

-

Decrypt: $M = 23^{27} \ \text{mod} \ 55 = 12$

Why is it secure?

If someone knows $n$ and $e$:

- They can encrypt messages to you.

- But they can’t easily find $d$ without knowing $\varphi(n)$.

- And to get $\varphi(n)$, they must factor $n$ into $p$ and $q$.

- With large enough primes (hundreds of digits long), factoring is practically impossible with today’s computers.

RSA is a beautiful mix of:

- Simple number theory,

- Clever key sharing,

- And hard computational problems.

Simon Singh’s padlock analogy nails the intuition, but the real magic is in how $e$ and $d$ are linked by $\varphi(n)$, while $n$ acts as the public padlock.

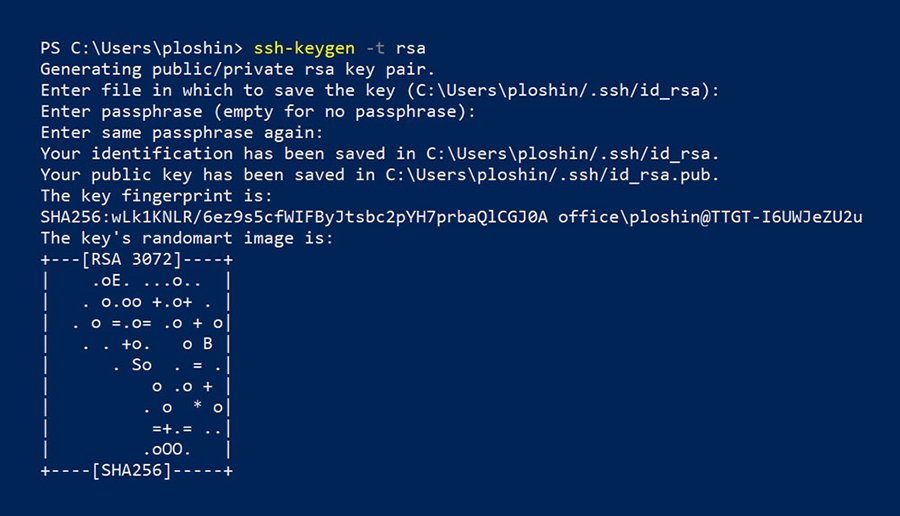

Figure 1: Creating an SSH key in terminal using ssh-keygen. The command also displays the public key’s fingerprint. The fingerprint is a short sequence of bytes generated by applying a cryptographic hash function (like SHA256) to the generated key. The fingerprint is used to verify the identity of the key. It is not used for encryption or decryption.

Figure 1: Creating an SSH key in terminal using ssh-keygen. The command also displays the public key’s fingerprint. The fingerprint is a short sequence of bytes generated by applying a cryptographic hash function (like SHA256) to the generated key. The fingerprint is used to verify the identity of the key. It is not used for encryption or decryption.

From RSA Theory to Practice: ssh-keygen

So far, we’ve seen the math behind RSA - two primes, $n=pq$, Euler’s totient $\varphi(n)$, the exponents $e$ and $d$. But how does this translate into something real, like the SSH keys we use every day?

The command you’ve probably typed before is:

ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096

Let’s break it down:

1. Where do you create the keys?

You should always generate the key pair on your own computer (your client machine), not on the server.

Reason: Your private key is like your house key. You don’t want to hand it to anyone else (including the server). You create it locally and keep it safe.

After you run ssh-keygen, you’ll usually get two files:

~/.ssh/id_rsa→ Private key (keep this secret, never copy it anywhere).~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub→ Public key (safe to share).

2. Where do the keys go?

-

Private Key (your secret): Stays only on your personal computer (in

~/.ssh/id_rsa).- Never upload it to the server.

- Never email it.

- Never share it.

-

Public Key (shareable): This goes to the server you want to connect to. Specifically, it should be added to the file:

~/.ssh/authorized_keyson the server (inside your user account).

You can copy it using:

ssh-copy-id user@server

or manually appending the contents of id_rsa.pub to ~/.ssh/authorized_keys on the server.

3. What happens when you log in?

When you run:

ssh user@server

- The server checks your

authorized_keysfile for your public key. - It encrypts a challenge using that key.

- Your client uses your private key to prove you can decrypt the challenge.

- If it matches, you’re in - no password needed.

4. Why this design?

- You can copy the same public key to multiple servers.

- You keep one private key on your laptop.

- This way, you carry your “identity” with you, instead of managing passwords on every server.

Common Mistakes

-

Generating keys on the server: If you do this, your private key lives on the server. That defeats the purpose, because you won’t be able to log in from your laptop later.

-

Copying the private key to the server: Never do this! Only the public key belongs on the server.

So in short:

- Create keys on your computer.

- Keep the private key local.

- Copy only the public key to the server.

That’s how RSA moves from math (primes, exponents) into a real-world workflow you use every day when typing ssh.

Next time you see “🔒” in your browser or you’re typing ssh to login, remember: somewhere, giant primes are keeping your secrets safe.

Fin.