On the cover: Decorative

For nearly a decade, if you wanted a computer to identify a cat in a picture, you had one reliable tool: The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). CNNs were the undisputed kings of Computer Vision. They were dependable, they understood that pixels next to each other usually relate to each other (locality), and they didn’t ask for much other than a decent GPU and some ImageNet data.

Then, around 2017, the Natural Language Processing (NLP) folks started throwing a massive party with something called “Transformers”. They were generating poetry, translating languages instantly, summarizing long documents and creating eerily coherent chatbots.

The Computer Vision community looked over the fence, saw the NLP party, and thought, “Wait a minute. If a sentence is just a sequence of words, isn’t an image just a sequence of pixels? Can we crash that party?”

Enter the Vision Transformer (ViT). This is the story of how we stopped treating images like 2D grids and started treating them like a very strange foreign language.

Why We Loved (and Tolerated) CNNs

Before we dive into tokens, let’s pour one out for the CNN.

CNNs work because they possess a brilliant “inductive bias”: a baked-in assumption about the world. They assume that a pixel’s relationship with its immediate neighbors is paramount. They use little sliding windows (kernels) to scan an image, detecting edges, then textures, then cat ears, then entire cats.

This is highly efficient. But it has a flaw: A CNN looks at the world through a soda straw. To understand the relationship between a pixel in the top-left corner and one in the bottom-right, the information has to travel through layer after layer after layer, slowly dilating that soda straw until it sees the whole picture. CNNs are great at seeing the trees, but sometimes struggle to grasp the concept of a “forest” until very late in the game.

The paradigm shift was “Attention is All You Need” (even for pictures). The Transformer architecture doesn’t care about locality. It doesn’t have sliding windows. It relies entirely on the Self-Attention mechanism.

If a CNN is a librarian painstakingly indexing books shelf by shelf, a Transformer is a hyper-caffeinated researcher running wildly through the library, instantly connecting a footnote in a history book to a diagram in a physics journal across the room.

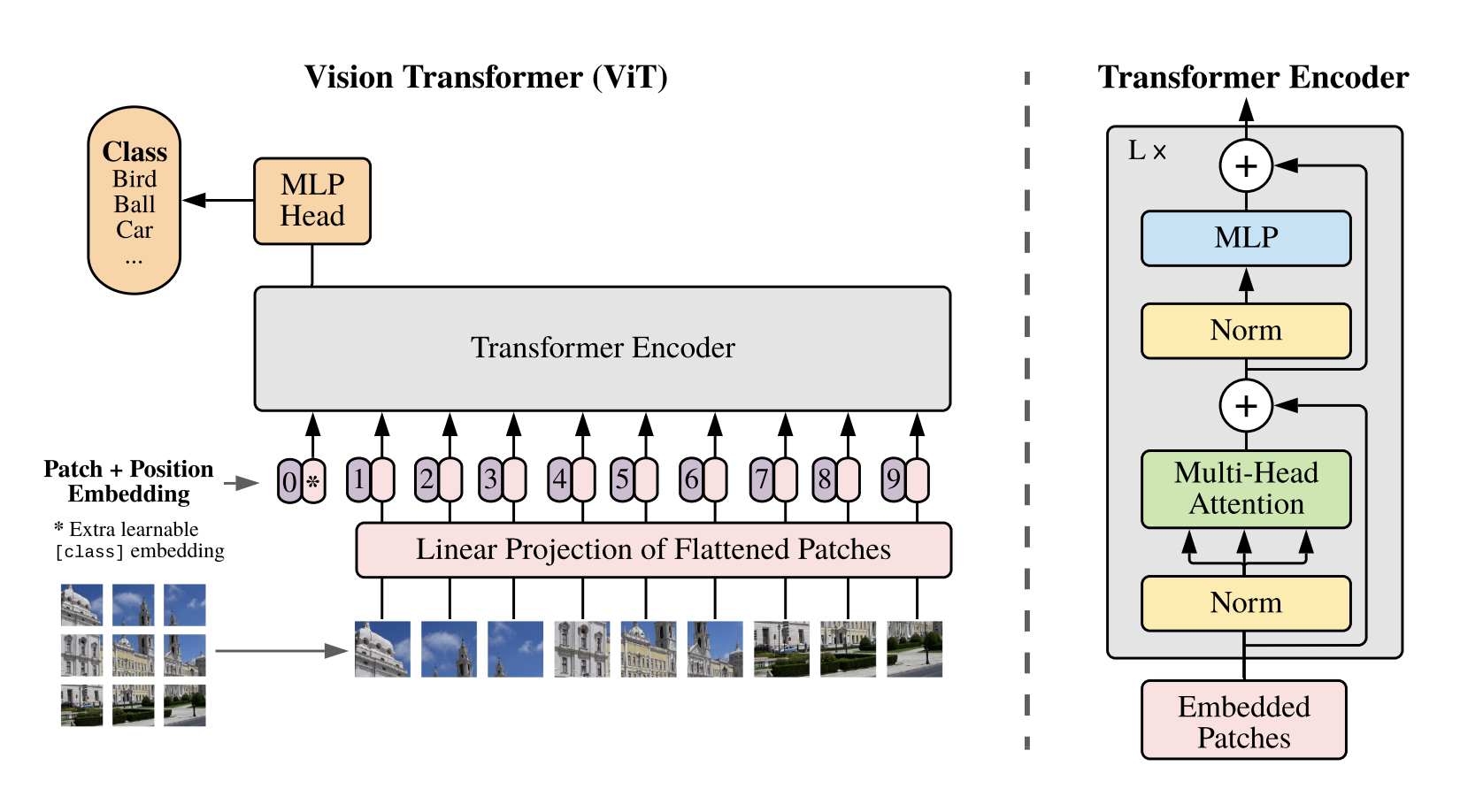

The breakthrough idea of the original Vision Transformer paper An image is worth 16X16 words, Dosovitskiy et al., 2020 was quite simple: Don’t change the Transformer architecture. Change the data. If the model wants a sequence of tokens (like words in a sentence), let’s beat the image into a sequence of tokens.

The Mechanics: How to Turn a Cat into a Paragraph

This is the technical heart of the operation. How do we go from a 224x224 JPEG to something say BERT can understand?

Step 1: The Butcher Shop (Patchification)

Let’s say you have an image of a cat. The first thing ViT does is take a pizza cutter and slice that image into perfect square grid—say, 16x16 pixels each. If your image is 224x224, you end up with 196 little squares (patches).

Figure 1: Original ViT architecture. Source: Dosovitskiy et al., 2020

Figure 1: Original ViT architecture. Source: Dosovitskiy et al., 2020

Formally:

- Input image: $H \times W \times C$

- Patch size: $P \times P$

- Number of patches: $\frac{H \times W}{P^2}$

So an image becomes:

\[X \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D}, \quad \text{where } N = \frac{H \times W}{P^2}\]Example,

Typical configs:

| Image | Patch | Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| 224² | 16² | 196 |

| 224² | 32² | 49 |

| 384² | 16² | 576 |

Step 2: The Mathematical Smoothie (Linear Projection)

A 16x16 RGB patch is still just raw pixel data (16 x 16 x 3 color channels = 768 numbers). The Transformer can’t read that.

So, we flatten that patch into a long vector and shove it through a linear projection layer. Think of this as squashing the raw visual information into a dense, mathematical smoothie that represents the essence of that patch.

Formally, if $X_p \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times (P^2 C)}$ is the matrix of flattened patches, ViT computes:

\[E = X_p W_E + b_E,\quad W_E \in \mathbb{R}^{(P^2 C)\times D}\]mapping each patch into a $D$-dimensional token embedding.

In practice, this linear projection is often implemented as a convolution:

\[\text{Conv2D}(C \rightarrow D,; \text{kernel}=P,; \text{stride}=P)\]which is mathematically equivalent to patch extraction + projection.

Congratulations! That smoothie is now a “token.” We have converted pixels into the visual equivalent of a word.

Step 3: The Location Sticker (Positional Embedding)

Here is the Transformer’s Achilles’ heel: It has absolutely no sense of space. If you feed it the puzzle pieces, it doesn’t know that the “ears” token belongs above the “whiskers” token. It treats the image like a bag of words.

To fix this, we must add Positional Embeddings. We can add a unique vector, often sine and cosine waves of different frequencies; you can also use RoPE which I have explained in a previous blog to each token that says, “Hey, I belong in row 2, column 3.” Now the model knows the geometry.

Essentially,

\[Z_0 = X_{\text{patch}} + E_{\text{pos}}\]Where $E_{\text{pos}} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D}$.

Step 4: The Special Sauce (Multi-Head Self-Attention)

We take our sequence of 197 tokens (196 patches + one special “[CLS]” token to summarize the whole image) and shove it into the Transformer encoder block.

\[\text{[CLS]} + \text{patch}_1 + \text{patch}_2 + \dots + \text{patch}_N\]The math relies on three vectors created from each token: Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V). Each transformer layer computes:

\[Q = XW_q \\ K = XW_k \\ V = XW_v \\ \text{Attention} = \text{softmax}(QK^T / \sqrt{d}) V\]Inside the attention mechanism, every single patch looks at every other patch simultaneously. There’s a difference in the attention between the vision transformers and text transformers. In text, we perform masked self-attention because we want the model to see only the past tokens to predict the next token. Whereas here, we want the vision tokens to attend fully to each patch without any masking!

This means that a ViT has a global receptive field instantly. The top-left pixel can talk to the bottom-right pixel immediately. No soda straws required.

The Hangover: The Early Cons of ViTs.

When the ViT paper dropped, it wasn’t an immediate slam dunk. There were several problems:

-

The Data Hunger: Because ViTs lack the inductive bias of CNNs (they don’t assume locality), they have to learn how to see from scratch. The original ViT only beat state-of-the-art ResNets when pre-trained on Google’s private JFT-300M dataset (that’s 300 million images). On standard ImageNet (1.3M images), it actually underperformed CNNs. This tells us that ViTs are data-hungry monsters.

-

The Computational Cost: Calculating attention means every token talks to every other token. If you double the image resolution, the number of patches quadruples (since its $P^2$), and the computational cost of attention grows quadratically. High-res images brought GPUs to their knees.

The Evolution: Fixing the Beast

The research community, realizing they were onto something huge, quickly addressed the flaws and also proposed many variants to improve the ViT.

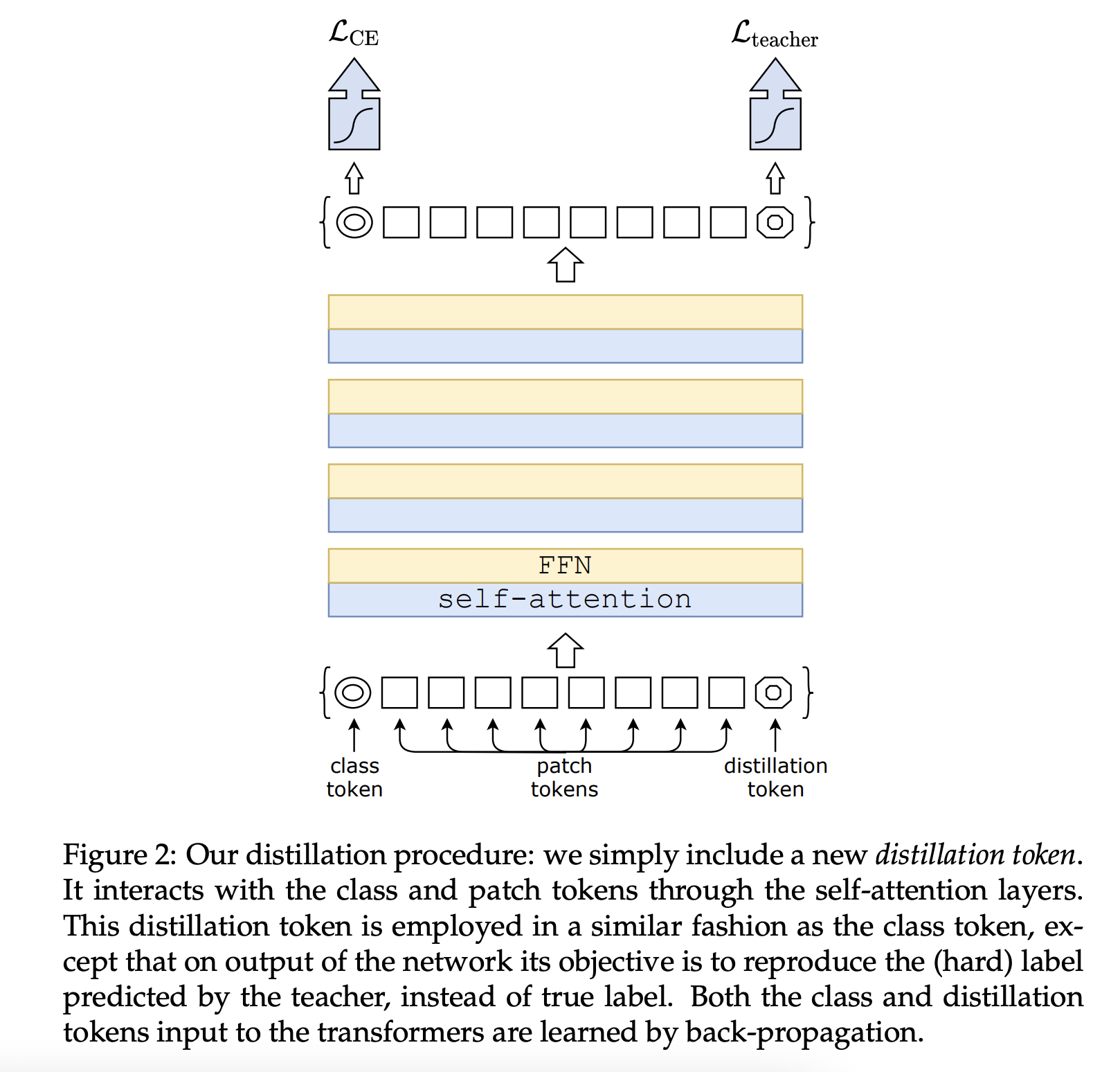

- DeiT (Data-efficient Image Transformers, 2020): Meta AI figured out how to train these things without Google-sized datasets in the paper DeiT They used knowledge distillation, basically having a smart, pre-trained CNN act as a teacher, giving the junior ViT hints during tests. Also used strong augmentations like Mixup, CutMix and RandAugment.

Figure 2: DeiT architecture. Source: DeiT

Figure 2: DeiT architecture. Source: DeiT

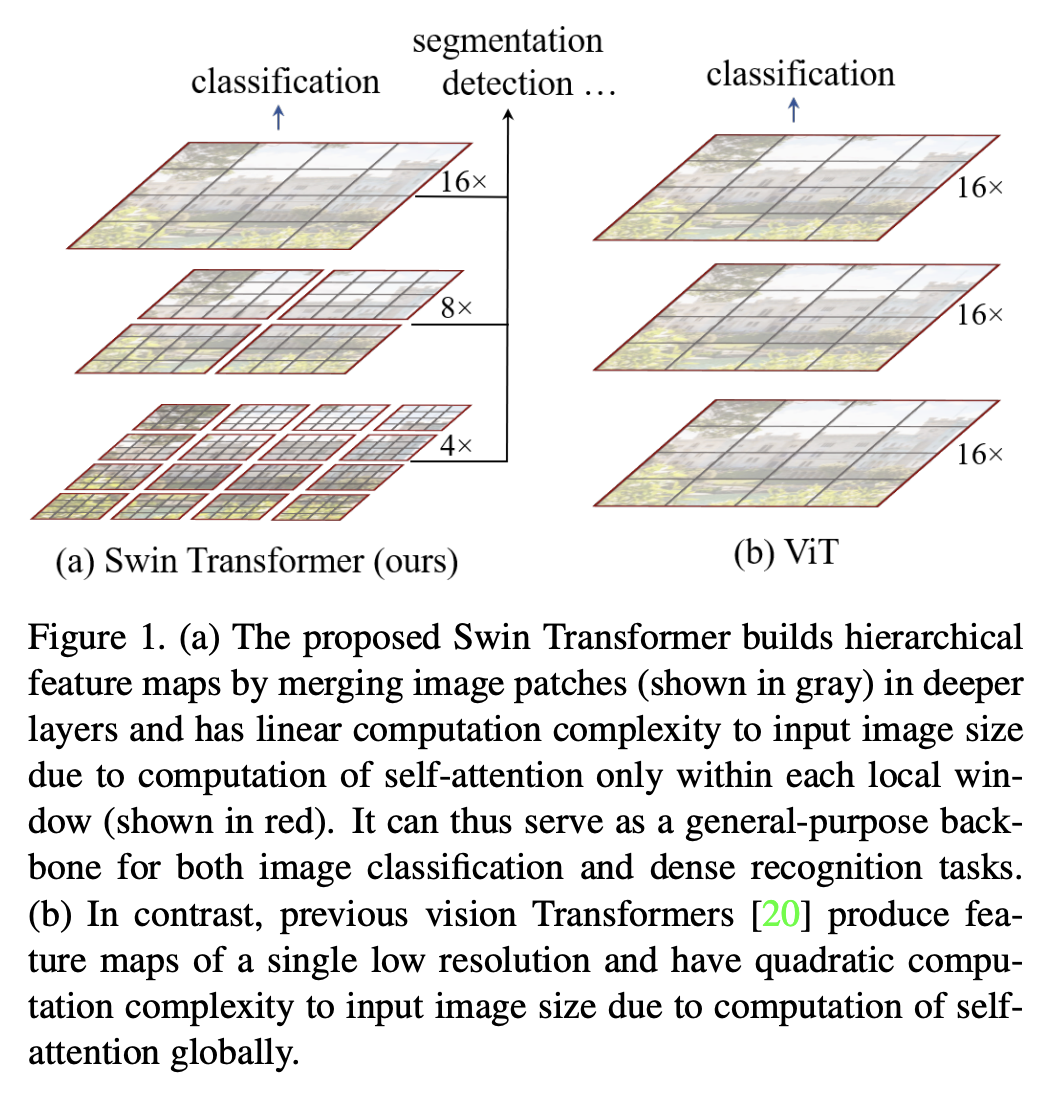

- Swin Transformer (Hierarchical ViT, 2021): Microsoft said, “Hey, maybe those CNN guys were onto something with those sliding windows.” The Swin Transformer re-introduced locality by computing attention only within local windows, then shifting those windows and zooming out in later layers. It brought back the hierarchy of CNNs while keeping the power of attention.

Figure 3: Swin architecture. Source: Swin Transformer

Figure 3: Swin architecture. Source: Swin Transformer

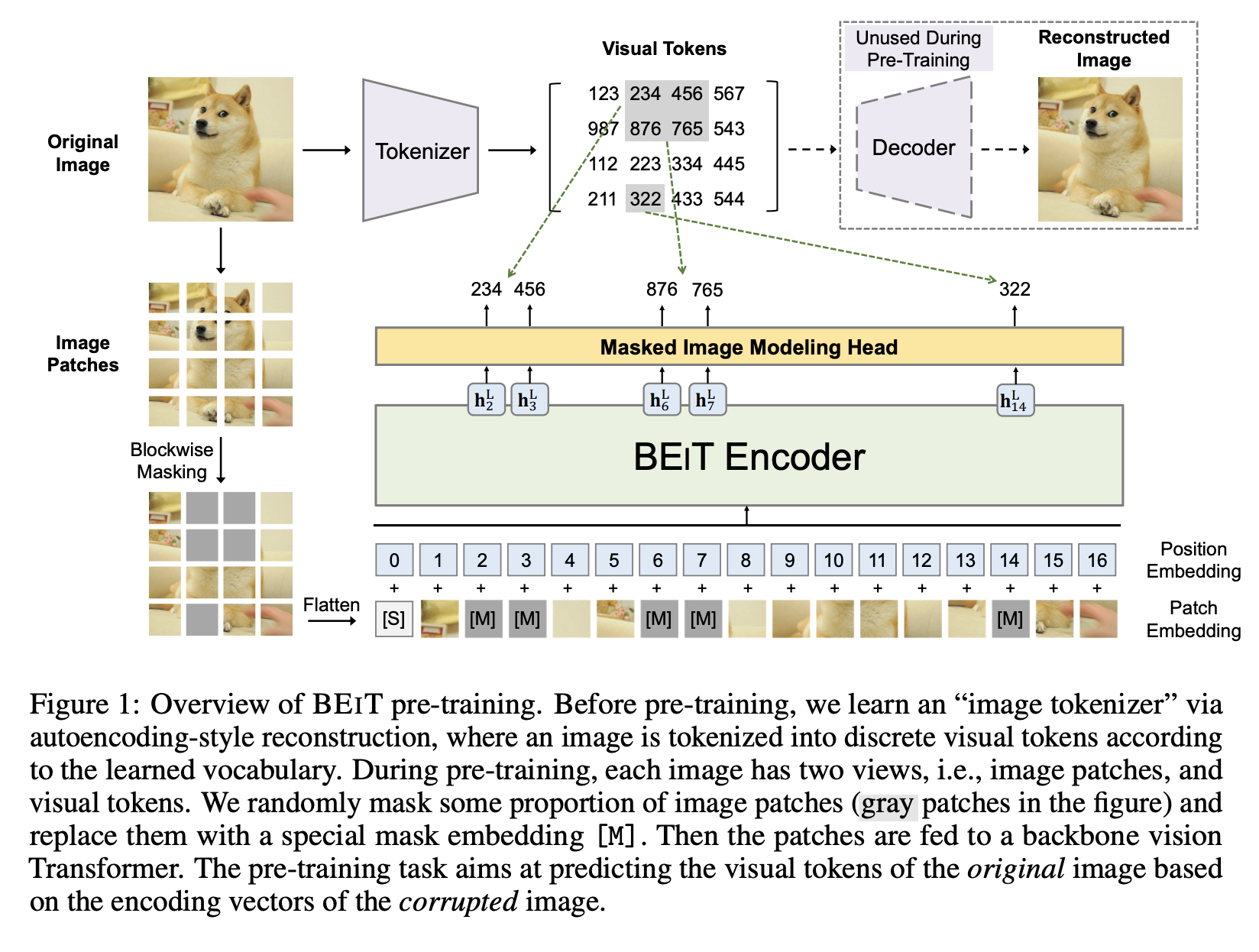

- BEiT (BERT for Images, 2021): Microsoft leaned hard into NLP analogies with BEiT. Images were tokenized using a VQ-VAE, and the ViT was trained to predict masked visual tokens, just like BERT predicts masked words. This was the first serious attempt to bring masked language modeling to vision.

Figure 4: BEiT architecture. Source: BEiT

Figure 4: BEiT architecture. Source: BEiT

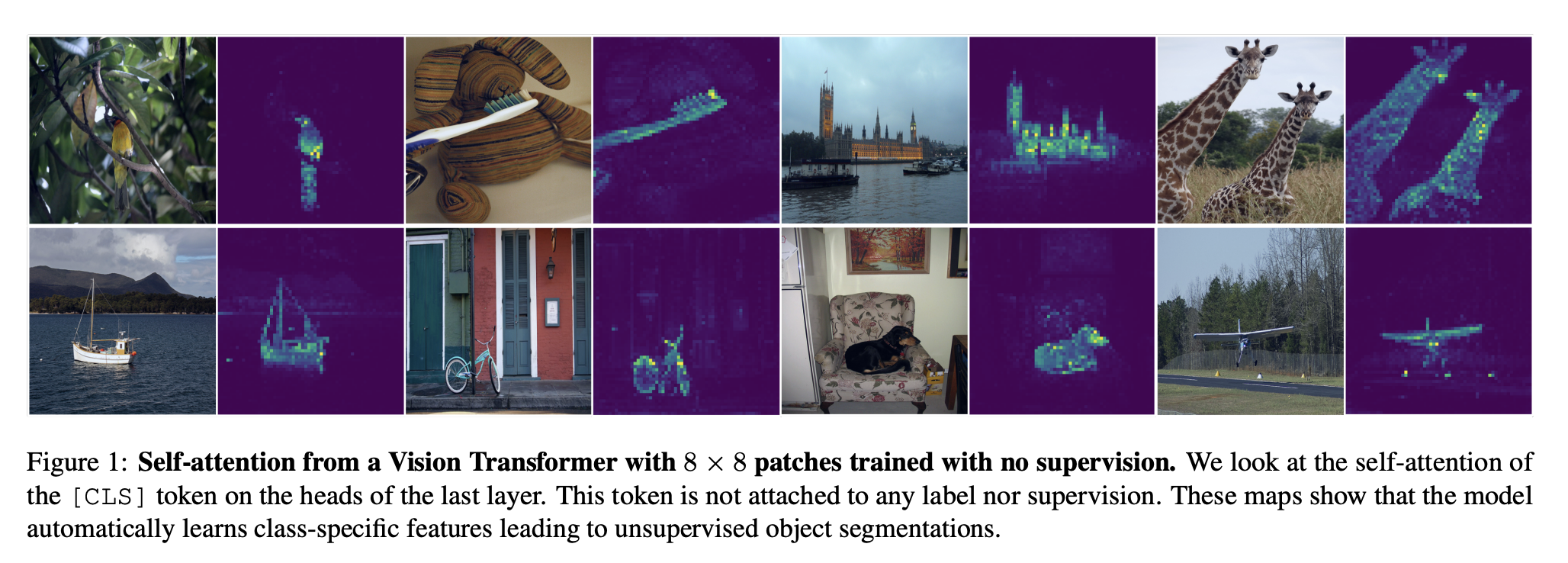

- DINO (Self-Distillation, 2021): Facebook AI surprised everyone with DINO: Emerging Properties in Self-Supervised Vision Transformers, showing that ViTs could learn meaningful object structure without any labels. Using student–teacher self-distillation, DINO-trained models spontaneously learned segmentation-like attention maps. No supervision, no problem.

Figure 5: DINO architecture. Source: DINO

Figure 5: DINO architecture. Source: DINO

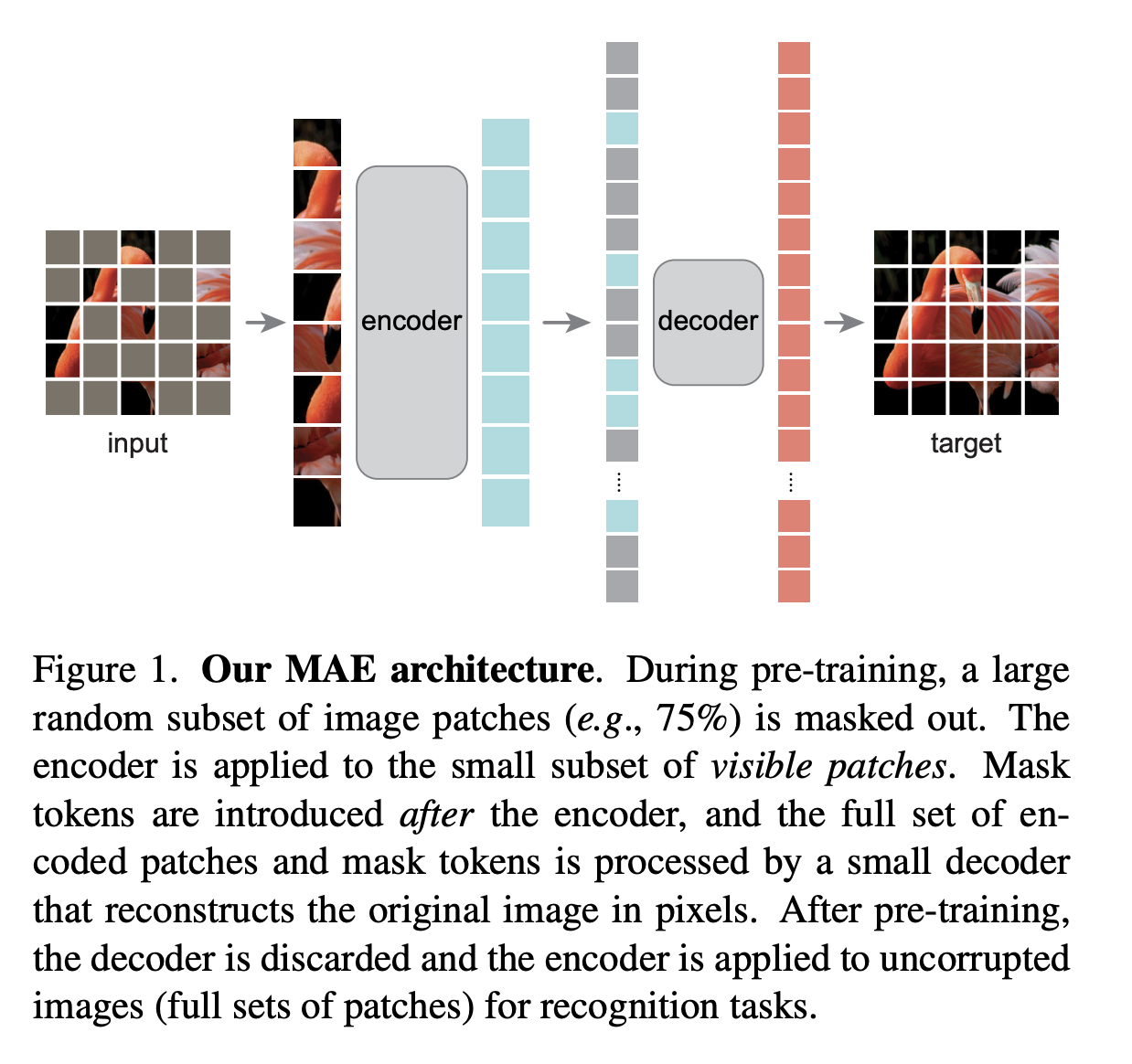

- MAE (Masked Autoencoders, 2021): Kaiming He and team struck gold with MAE. Instead of predicting discrete tokens, MAE masked around 75% of patches and trained the model to reconstruct them. A lightweight decoder plus a heavy encoder made pretraining extremely efficient. This quickly became the default recipe for large ViT pretraining.

Figure 6: MAE architecture. Source: MAE

Figure 6: MAE architecture. Source: MAE

-

ConvNeXt (The Reality Check, 2022): After everyone boarded the Transformer hype train, Meta released ConvNeXt: Revisiting ConvNets for the 2020s. They modernized CNNs using ViT-style tricks—LayerNorm, large kernels, GELU, and better optimization—and showed that “old-school” convolutions could still compete. One uncomfortable takeaway from this paper was that a big chunk of ViT’s success came from better training, not just attention.

-

CLIP (Vision Meets Language, 2021): OpenAI changed the rules with CLIP: Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. Trained on hundreds of millions of image–text pairs, CLIP aligned vision and language in a shared embedding space. Zero-shot classification suddenly worked. Labels were optional. The internet became the dataset. We’ll speak more about this in our next post.

Implications: The Great Unification

Why does any of this matter? Were we just chasing a 0.5% accuracy bump on ImageNet?

No. The shift from pixels to tokens is about unification.

Before ViTs, we had different architectures for different senses. CNNs for images, Transformers for language and perhaps LSTMs for audio.

Now, everything is a token. An image patch is a token. A text word is a token. A snippet of audio spectrogram is a token.

This is why we now have massive Multimodal Foundation Models like GPT-5 or Gemini-3. Because ViTs proved that visual data could be processed by the same engine that processes text, we can now dump images and text into the same massive network and let it figure out the correlations.

I wouldn’t say CNNs are dead yet; they are still highly efficient and useful on edge devices. But the Vision Transformer proved that sometimes, to see the big picture, you have to smash it into little pieces and treat it like a language.

Conclusion

Vision Transformers (ViTs) reframed perception as a token-processing problem. Instead of sliding filters over pixels, they convert images into discrete units and let attention learn structure from data.

Images stopped being treated as grids and started being treated as sequences. This shift has fundamentally changed how spatial reasoning, scale, and abstraction emerge in vision models, especially when you have large amounts of data.

And now you know. Fin.