On the cover: Pixels to tokens

In our last post, we spoke about how the Vision Transformer (ViT) took the candy away from CNNs. We learned that if you slice an image into patches and flatten them, you can treat an image just like a sentence. And a sequence of pixel-patches becomes a sequence of tokens.

This enables the ViT to look at an image and output a label class_id: 284 (“Siamese Cat”). All this is good, but while ViTs taught computers to “read” images, they are still essentially mute.

Meanwhile, in the building next door, NLP scientists were using Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-3 were writing poetry and coding in Python. But they were blind. They had never seen a sunset, only read descriptions of one.

The obvious question asked by researchers around 2021 was: “We have a model that understands vision (ViT) and a model that understands language (LLM). What happens if we introduce them to each other?”

Welcome to the era of Vision-Language Models (VLMs). This is the story of how AI learned to see and speak at the same time.

The Problem: The Tower of Babel

You might think, “Just glue the ViT to the LLM and be done with it.”

It’s not that simple. Even though both models use the Transformer architecture, they speak completely different mathematical languages.

- The ViT spits out vectors that represent edges, textures, and shapes.

- The LLM spits out vectors that represent grammar, logic, and vocabulary.

If you feed ViT output directly into an LLM, it looks like gibberish. It’s like trying to plug a Nintendo cartridge into a toaster. We needed a “Rosetta Stone”—a way to align these two worlds.

The Matchmaker (CLIP)

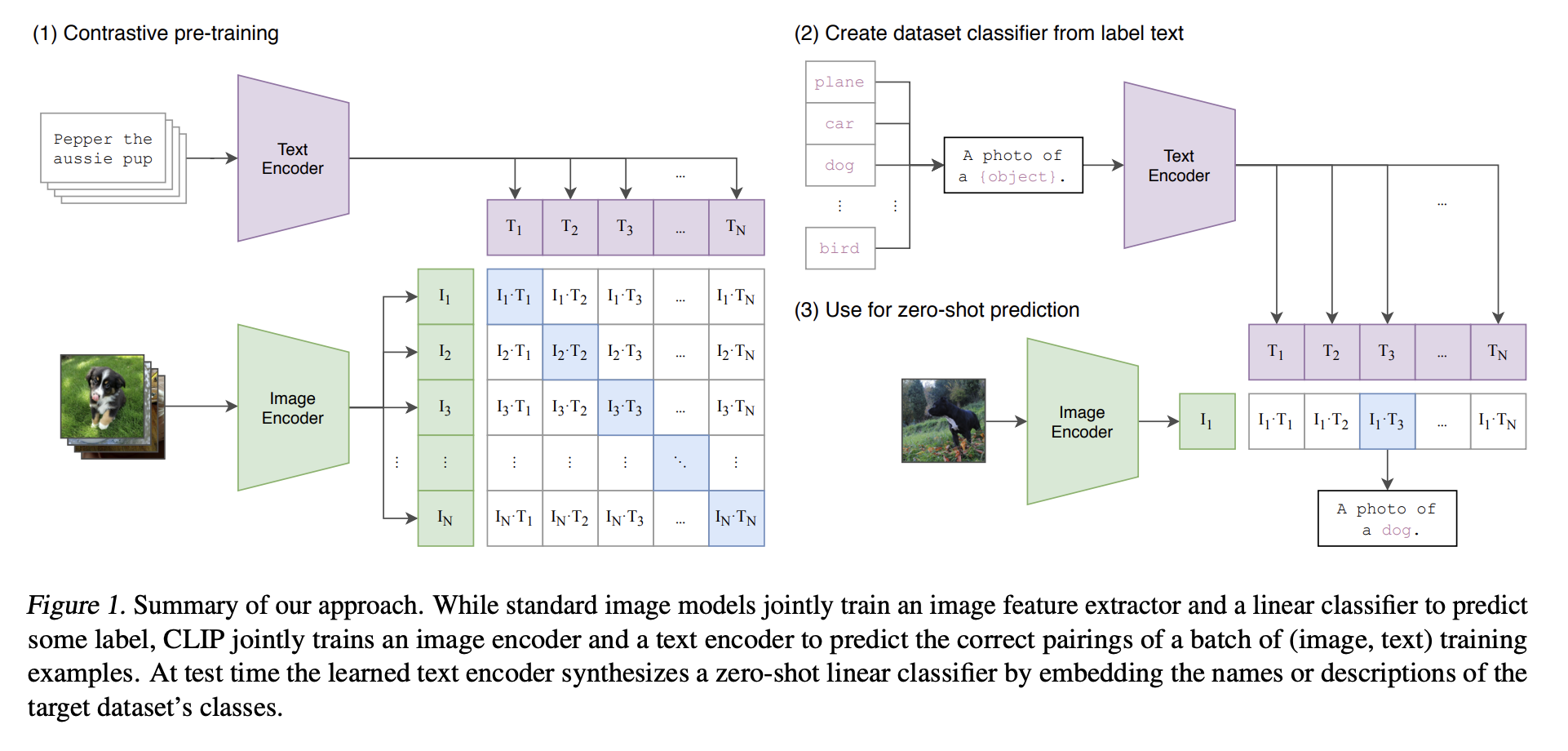

Before we could get models to chat about images, we had to get them to agree on what images were. The breakthrough came from OpenAI in 2021 with CLIP: Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision.

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining) wasn’t built to generate text. It played a massive game of “Match the Caption.”

Imagine you have a batch of N images and N text captions.

- Run images through an Image Encoder (like a ViT).

- Run texts through a Text Encoder (like a mini-BERT).

- The Goal: The model must figure out which text belongs to which image.

Mathematically, it maximizes the dot product (similarity) between the correct image-text pairs and minimizes it for the incorrect ones. This forces the model to learn a shared embedding space. Essentially,

\[\frac{e^{\text{similarity score of a correct pair}}}{\sum_{\text{all incorrect pairs}}e^{\text{similarity score of pairs}}}\]More mathematically,

\[\mathbb{L} = \sum_{i=1}^{|\mathbb{B}|} \log \frac{e^{x_i^\top y_i / \tau}} {\sum_{j=1}^{|\mathbb{B}|} e^{x_i^\top y_j / \tau}} + \sum_{i=1}^{|\mathbb{B}|} \log \frac{e^{x_i^\top y_i / \tau}} {\sum_{j=1}^{|\mathbb{B}|} e^{x_j^\top y_i / \tau}}\]where $x_i$ is an image feature vector and $y_j$ is a text feature vector, $\mathbb{B}$ is the mini-batch size of images and texts, and $\tau$ is a temperature parameter.

The loss is computed twice, one for every image and one for every text.

- Image -> Text

- Text -> Image

Softmax forces every image to compete against all other texts in the batch.

Figure 1: CLIP architecture. Source: CLIP paper

Figure 1: CLIP architecture. Source: CLIP paper

Thanks to CLIP, the vector for “cat” (text) and the vector for a picture of a cat (image) pointed in the same direction. The barrier between image and language was broken.

A better Matchmaker (SigLIP)

CLIP had one major issue. Imagine for a given image there are multiple captions that are relevant:

- “A dog running”

- “A corgi in a park”

- “A small brown dog outdoors”

Softmax assumes only one is correct within the batch. That normalization term:

\[\sum_{j=1}^{|\mathbb{B}|} e^{x_i^\top y_j}\]forces captions to compete with each other.

If two captions are semantically similar (dog vs corgi), they hurt each other’s probability. The batch becomes a zero-sum game.

This leads to three problems:

- You need carefully curated batches

- You need very large batch sizes

- You must compute the loss twice

Sigmoid Loss for Language-Image Pre-Training (SigLIP) from Google Research asks a radically simpler question:

Instead of “Which caption in this batch matches this image?” Why not ask: “Does this image match this caption — yes or no?”

Softmax -> Sigmoid

Instead of multi-class classification over the batch, SigLIP treats every image-text pair as a binary classification problem.

\[\mathbb{L}_{ij} = y_{ij} \log \sigma(x_i^\top y_j) + (1 - y_{ij}) \log (1 - \sigma(x_i^\top y_j))\]Where:

- $y_{ij} = 1$ if image $i$ matches text $j$

- $y_{ij} = 0$ otherwise

- $\sigma(\cdot)$ is the sigmoid function

But here’s the twist. Even SigLIP is still a two-tower model.

CLIP and SigLIP both learn:

“This whole image matches that whole sentence.”

It does NOT learn: “This part of the image explains this part of the sentence.”

No token-level interaction. No compositional reasoning. No step-by-step grounding. Two towers. No bridge. Which brings us to actual conversational/generative VLMs.

The Conversationalist (LLaVA & Friends)

CLIP was great at matching, but it couldn’t write you a poem about a salad. To do that, we needed Generative VLMs. This generation of models used cross-attention to fuse modalities inside Transformers.

The current standard architecture (popularized by models like LLaVA—Large Language and Vision Assistant) is quite simple. It’s essentially a “Frankenstein” model stitched together from three parts:

\[Tokens_{vision} = P(V(I)) Tokens_{text} = E(T) Output = LLM(Tokens_{vision}; Tokens_{text})\]Where:

- $V(I)$ = Vision encoder

- $P$ = Projection layer

- $E(T)$ = Tokenizer + Embeddings

- $LLM$ = Language decoder

So essentially,

-

The Eyes (Vision Encoder) We take a pre-trained Vision Transformer (usually CLIP’s vision encoder or Google’s SigLIP). We pass the image through it to get those “patch tokens” we discussed in the last blog. Status during training: Usually Frozen (we don’t want to break the eyes).

-

The Brain (The LLM) We take a pre-trained LLM (like Vicuna, Llama 3, or Mistral). This provides the reasoning, grammar, and world knowledge. Status during training: Frozen initially, then Fine-tuned later.

-

The Translator (The Projector) This is the magic glue. The output of the Vision Encoder might have a dimension of 1024, but the LLM expects an input dimension of 4096. We insert a simple Linear Projection Layer (or a small MLP) that translates “Visualspeak” into “LLMspeak.”

-

The Flow: We concatenate these visual tokens with text tokens. The LLM takes this combined sequence and just predicts the next token, exactly like it always does. It doesn’t even know it’s “seeing” an image; it just thinks it’s reading a very strange language that happens to describe a visual scene perfectly.

Cross-Attention Mechanism

Given:

- Text queries (Q_T)

- Image keys/values (K_I, V_I)

We compute:

\[\text{Attn}(Q_T, K_I, V_I) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{Q_T K_I^T}{\sqrt{d}} \right)V_I\]Now text tokens attend directly to visual tokens. Language can “look” at pixels. This is multimodal grounding part. If you look at the LLaVA paper, you’ll see the training is split into two distinct stages. This is crucial for stability.

Stage 1: Vision Pre-training

- Goal: Teach the Vision Encoder to see the world.

- Data: Image-Caption pairs (e.g., “A cat on a mat”).

- What learns?: Only the Vision Encoder. The Projector and LLM are frozen.

- Result: The Vision Encoder learns to see the world.

Stage 2: Vision Language Alignment

- Goal: Teach the “Projector” to translate.

- Data: Simple Image-Caption pairs (e.g., “A cat on a mat”).

- What learns? Only the Projector. The Vision Encoder and LLM are frozen.

- Result: The LLM stops seeing the image tokens as noise and starts recognizing them as concepts.

Stage 3: Visual Instruction Tuning

- Goal: Teach the model to follow instructions and act like a chatbot.

- Data: Complex conversations.

- User: “What is unusual about this image?”

- Assistant: “The man is ironing a sandwich, which is highly atypical…”

- What learns? The Projector and the LLM.

- Result: A model that can reason, count, and explain visual data.

Why This Matters: The End of “Just Seeing”

We are moving away from specific tools. We used to have one model for “Is this a hotdog?” and another for “Read this receipt.”

VLMs are generalist agents.

- You can show them a picture of your fridge and ask for recipes.

- You can show them a screenshot of code error logs and ask for a fix.

- You can show them a dashboard and ask for a summary of trends.

Why do VLMs scale so well? Because language is compressed human knowledge. Every caption encodes: Physics, Culture, Intent, Affordances, Causality. “A chair” is not pixels. It is: “Something you can sit on.” That’s functional semantics. VLMs learn affordances, not just appearances.

The Evolution:

There were many variants of VLMs proposed in the research community.

Conclusion

If the Vision Transformer was about turning images into words, the Vision-Language Model is about turning images into dialogue.

We have effectively given LLMs eyes. By simply projecting visual vectors into the language space, we tricked the text model into hallucinating a vision system. And it works beautifully.

The future isn’t just “Computer Vision” anymore. It’s Multimodal AI.

And now you know. Fin.