On the cover: The concept of low-rank adaptation visualized as dimension reduction

If you’ve been paying any attention to the AI world lately, you might have noticed these large language models (LLMs) getting increasingly heavy and fat. GPT-4 is rumored to have 1.76 trillion parameters, which is approximately the same as the number of times I’ve contemplated whether my coffee needs another shot of espresso. The answer, by the way, is always yes.

But here’s the problem: fine-tuning these chonky models for specific tasks requires massive computational resources. Enter LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) - the diet pill that language models have been desperately waiting for. In this post, I’ll dive into the surprisingly simple mathematics behind LoRA. Brace yourselves for some matrix algebra that’s more exciting than it sounds, I promise :)

The Weight Problem

Let’s set the stage. A pre-trained language model like GPT-4, Gemini or LLaMA has a bunch of weight matrices $W_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times k}$, where $d$ is the number of rows and $k$ is the number of columns. During traditional fine-tuning, let’s say we updated these full matrices to $W = W_0 + \Delta W$, where $\Delta W$ represents all the changes we made to the weight matrix during fine-tuning (whose dimension is also $\mathbb{R}^{d \times k}$).

For these massive models, the dimensions $d$ and $k$ can be in thousands, creating weight matrices with millions of parameters. For example, a weight matrix of size $4096 \times 4096$ has approximately 16.8 million parameters. Fine-tuning all these parameters means:

- Storing the full model weights (hundreds of GB)

- Computing gradients for all parameters (computationally expensive)

- Updating all parameters (memory intensive)

- Storing a separate copy of the model for each fine-tuned version (storage nightmare)

The LoRA Insight

Here’s where the mathematical genius of LoRA comes in. The key insight of LoRA is that $\Delta W$ often has a low “intrinsic rank” - a fancy way of saying that despite the giant size of $\Delta W$, the actual information contained in these updates lives in a much lower-dimensional space.

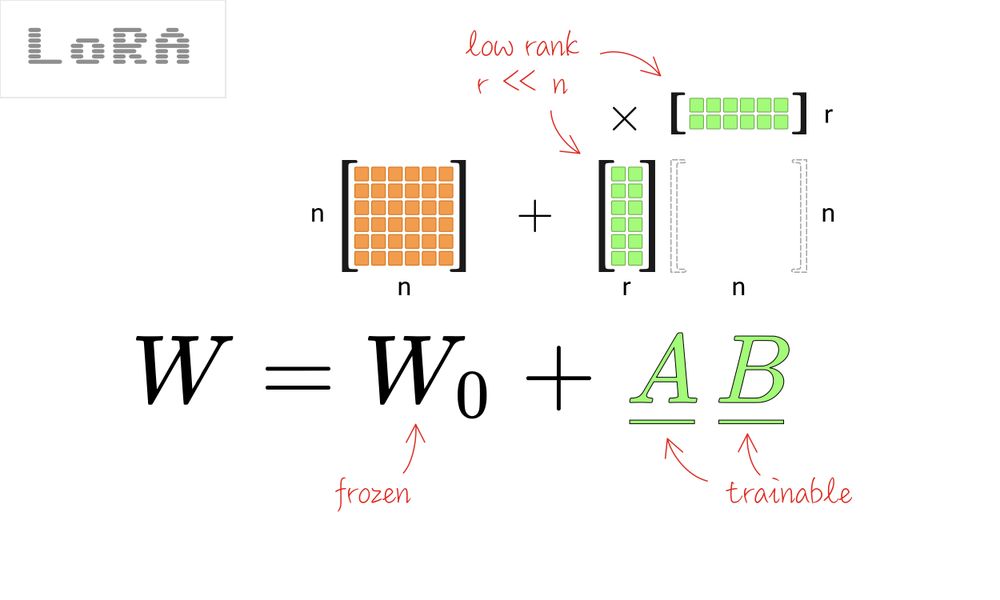

Instead of directly learning $\Delta W$, LoRA parameterizes the update as:

\[\Delta W = BA\]where $B \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times r}$ and $A \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times k}$, with the rank $r \ll \min(d, k)$.

This gives us $W = W_0 + BA$, where we only train the parameters in $A$ and $B$ while keeping $W_0$ frozen.

Let’s do some quick math to see why this is amazing. For our example weight matrix of size $4096 \times 4096$:

- Full fine-tuning: 16.8 million trainable parameters

- LoRA with rank $r = 8$: $(4096 \times 8) + (8 \times 4096) = 65,536$ trainable parameters

That’s a 256x reduction! Elegant, isn’t it?

How Does LoRA Work?

During the forward pass in a transformer model with LoRA, our computation looks like:

\[h = W_0 x + \Delta W x\]Where $x$ is the input vector and $h$ is the output. With our reparameterized update, we can write the same things as,

\[h = W_0 x + BAx\]When we take the derivative, we only need to worry about A and B, i.e. $\frac{\partial L}{\partial A}$ and $\frac{\partial L}{\partial B}$, which are much smaller matrices compared to $W_0$, i.e, $\frac{\partial L}{\partial W_0}$. This means we’re essentially computing the same thing as we would in full fine-tuning, but with far fewer trainable parameters.

The beauty of this approach is that we’re not changing the original model at all - we’re just adding our low-rank adaptation matrices. This means:

- The original pre-trained weights stay intact

- We can switch between different LoRA adaptations by simply swapping $A$ and $B$ matrices

- We can even combine different LoRA adaptations by adding their effects

Figure 1: Schematic of LoRA applied to a transformer model

Figure 1: Schematic of LoRA applied to a transformer model

Initialization Magic

Here’s a neat trick from the LoRA paper. They initialize $A$ with random Gaussian values and $B$ with zeros. This means that at the beginning of training, $\Delta W = BA = 0$, so the model starts exactly from the pre-trained weights with no initial perturbation. It’s like starting your journey exactly where the original model left off, then carefully steering it in your desired direction.

The α Scaling Factor

The paper introduces an additional scaling factor $\alpha$ that helps control the magnitude of the update:

\[\Delta W = \frac{\alpha}{r}BA\]This factor helps normalize the variance of the weight update when we change the rank $r$. The authors found that this normalization allows them to use the same learning rate regardless of the rank. It’s like having an automatic gear system that adjusts based on how much dimensionality reduction you’re applying. Neat, huh?

Why Does LoRA Work So Well?

The million-dollar question: why can we get away with such a drastic parameter reduction? There are several hypotheses:

-

Intrinsic Low Dimensionality: The task-specific adaptations required for fine-tuning might naturally live in a low-dimensional subspace of the full parameter space.

-

Overparameterization: Large language models are heavily overparameterized, meaning much of their capacity is redundant.

-

Parameter Efficiency: Not all parameters in a model contribute equally to the model’s performance. LoRA focuses on finding the most impactful directions for parameter updates.

This reminds me of the old adage: “It’s not about working harder, it’s about working smarter.” LoRA is definitely the “work smarter” approach to fine-tuning.

Where to Apply LoRA?

You might be wondering - should we apply LoRA to all weight matrices in the model? The original paper experimented with applying LoRA to different components of the transformer architecture and found that:

- Applying LoRA to both attention query and value matrices ($W_q$ and $W_v$) worked well

- Adding LoRA to other matrices like $W_k$ (key) and $W_o$ (output) showed diminishing returns

So it seems that not all matrices are created equal when it comes to efficient fine-tuning. The query and value matrices appear to be the most “bang for your buck” in terms of adaptation capacity.

LoRA in Practice

The practical benefits of LoRA are enormous:

- Memory Efficiency: Fine-tune models on consumer GPUs that would otherwise require server-grade hardware

- Storage Efficiency: Store multiple fine-tuned versions of a model by just keeping different sets of small LoRA matrices

- Deployment Efficiency: Merge LoRA weights back into the original model or keep them separate, depending on your deployment constraints

- No Inference Slowdown: Unlike adapter methods that add extra layers, LoRA can be merged with the original weights for inference, resulting in no additional computational overhead

It’s like having your cake and eating it too, except the cake is a 175B parameter model and eating it doesn’t require a data center.

Conclusion

LoRA represents an elegant mathematical solution to the very practical problem of fine-tuning large language models. By exploiting the intrinsic low-rank nature of weight updates during fine-tuning, we can achieve comparable performance with orders of magnitude fewer parameters.

As language models continue to grow (and they show no signs of slowing down), techniques like LoRA will become increasingly important. They democratize access to fine-tuning, allowing researchers and practitioners with limited resources to adapt these powerful models to specific tasks and domains.

The next time you’re staring at your GPU with 40GB of VRAM and wondering how you’ll ever fine-tune that shiny new 70B parameter model, remember: you don’t need to get a bigger much expensive dress, just use the magic diet pill called LoRA.

Fin.